This is part 2 of a series on relational communication, equipping people to enter into relationships in a more healthy and loving way. I highly recommend starting with part 1 of this series as this post draws upon points already established in part 1.

My job involves leading culture change among diverse teams. After a year of listening to the staff I was supervising, I had learned a few things about them that were key to leading culture change among them.

We had to come up with a vision for our team, to be able to know and explain to ourselves and to others what made us us, what we did about our culture as a team, where were were going, and how we were going to get there. We were a year into this pandemic, past the worst of it, but still needing to get a sense of who we are and where we’re going, to inform what we do together.

We covered the goals of our national organization and of our smaller, more regional goals, but we still hadn’t decided who we were and what we going fro as an even smaller, more local area team. So how did I lead us into this process?

I listened. In past, larger work spaces, I listened when my staff said, “this isn’t working for me”, or “this is unmotivating”. So I learned what not to do. But how did I find out what to do?

I researched. After learning about my team, I found out what motivated them through having an expert take us through Cultural Intelligence (CQ) conversations and through discussions around the Enneagram. And then, I paid attention to the kinds of questions they asked to those they influenced.

The result? Instead of asking our organization-favorite question around team vision, which is “what do you want to see?”, I asked instead, “what makes you angry about the situation among the people you serve?” and “what feels unjust?” I asked these because my team consisted of people who are motivated by justice as God defines it and because they are all oriented toward seeing holistic wellness within communities, not just wellness for individuals. The conversation that resulted from these questions was natural, easy, genuinely involved the entire team, and within the conversation we were able to identify several practical directives for us to practice as a team going forward. More than that, we were all in agreement and were able to move forward together with momentum because we were all motivated by where we were going.

But what if I hadn’t paid attention and just asked the question, “what do you want to see?” The team would have been unmotivated, disinterested, and would have responded with very little, and it would have felt like pulling teeth to get to a vision we could all get behind and agree to. How do I know? Because the first time I did this exercise with them, that’s what happened!

In essence, whether I had asked “what do you want to see” or “what feels unjust”, I was asking the same question (eg – “what needs to change”), but I approached the question from a different angle. And that approach can make all the difference on whether someone shuts down or leans in.

So practically speaking, how do we do this? How do we find the angle that is most helpful for others? First, let’s start with why we should even care.

Communal Responsibility

Why do we care about communal responsibility?

- Because it’s Biblical (Exodus 21-23, Leviticus 26, Numbers 15-16, Deuteronomy 1:34-46, Deuteronomy 29-30; John 13-17, Acts 2, 4-6, and so on): Scripture is consistent in teaching that we are never just responsible for ourselves but also for our communities.

- Because it’s an expression of love for others and for our communities (and, per last part of this series, love is the center of all of this!)

- Because it can sustain communities and relationships better for longer: the reality is that when you die or leave or move, someone needs to keep it going or what you were doing will die or leave with you. Get ahead of it by doing things together in community!

- Because communities working together is more powerful than individuals working alone: “many hands make light work”

Our foundations for How we enter into relational communication well:

Again, these include a review from the last post in this series and draws from that foundation.

- LOVE is always, always the basis for healthy communication.

- Assume the best of others until they prove otherwise (see below).

- We are responsible for ourselves; how we act and how we react. Others are responsible for themselves; how they act and how they react. No one makes you do anything.

- 99% of the time, no one is trying to be a jerk, even when they hurt you. Usually, conflict with others comes from miscommunication or from misplaced expectations:

- Miscommunication: when you both say one thing but mean two different things, or when you both use one word but mean two different things.

- Misplaced expectations: didn’t have realistic or honestly communicated expectations of the other person going in

- It’s NOT about winning; it’s about deeper relationships.

- “So far as it depends on you, leave at peace with one another”. In conflict, you do your part; you cannot make them do theirs.

- If, as you are trying, they are unwilling to have the conversation, you can try a mediator (see below) or stop trying.

- If, as you are trying, they are unwilling to give any space to listen to you even when you ask for it, they may not be worth the effort.

- If you have tried but you get nowhere, try bringing in a mediator (neutral third party) – especially if your conflict is within an organizational structure. If, as you bring in a mediator, they are still unwilling to have the conversation or to listen, then either more people will be brought in or you will have done your part.

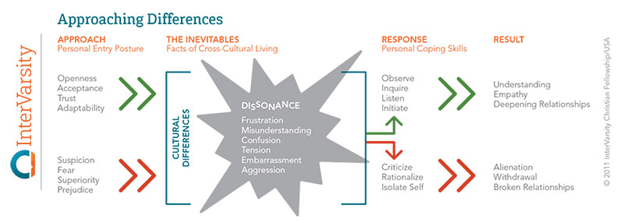

In the previous post, we talked about how you’re responsible for yourself – how you act and react – and others are responsible for themselves – how they act and react! We looked at the approaching differences tool and invited you to practice ‘green-lining’ for yourself in your own situations of conflict.

But what if you could actually do some things in order to create a space where you and others are more free (or more likely) to respond more graciously and more kindly to one another? What if you could actually anticipate problems beforehand and prevent a crisis beforehand?

Yes, that’s right – if you can learn how to green-line well for yourself, you can also lean into a whole new level of creating space for yourself and for others to more easily choose into green-lining. This requires some serious practice in listening, in learning who you are, and in learning who others are. In doing so, you can not only create and be in spaces where you and others thrive, but you can also create spaces that thwart crises before they happen. This is what I call ‘communal responsibility’, and, fair warning, this is not easy stuff!

Approaching Differences:

Communal Responsibility:

What motivates you and your culture?

Did you know that there are Different Motivators across the world? There are three main types of ‘motivators’ that people live by as their standard. Take a look through these three main motivators – which one would you say you fit best under, or if you feel like you fit multiple, what mix would you give yourself?

- Guilt/Innocence: typically western, typically individualist. Motivated primarily by what society has deemed legal/illegal.

- Example: you parked a car in the wrong place and get a parking ticket. You feel bad because you parked in the wrong place, and make a point to remember to pay the ticket to make it right.

- Shame/Honor: typically more communal cultures. Motivated primarily by what their community has decided brings glory or goodness upon their people.

- Example: you parked your car in the wrong place and get a parking ticket. You feel fine about this and may or may not pay the ticket, until a family member who you respect finds out about it and tells you to do better – so then you go and pay the ticket.

- Fear/Power: typically more isolated/tribal cultures. Motivated primarily by scarcity and by who has abundance of whatever society has deemed ‘powerful’.

- Example: you parked your car in the wrong place and get a parking ticket. Because you don’t feel that you have as much power as the police, you feel bad and dutifully pay the fine as soon as you can so as not to incur anything worse.

Are you in an Individual Culture or a Communal Culture?

Above, I mentioned individual and communal cultures. What do I mean by that?

- Individual: each person is first responsible for themselves

- Communal: each person is first responsible for their community, their ‘people’ (whomever that may be)

- Example: it’s March 2020 and people are telling you to stay home and wear masks. Do you hear this as something for you to do (or not do) as your own individual decision, or do you hear this as something to do (or not do) for the sake of your community? Which do you think of first?

Main point so far: not everyone values the same things you do! Take time to find out what they do value and what does motivate them before assuming they are like you.

Practicing Communal Responsibility:

- You are still responsible for how you act and react (and they are still responsible for how they act and react), but you can also act & react in such a way that curates a more healthy space for others to act & react.

- This sounds like mind-reading, but it’s not!

- Examples:

- Practice Framing: setting expectations/ground rules at the beginning (in classes, this is called a ‘syllabus’) of a group or a conversation.

- Removing accusatory and “you did” language; using subjective, situational language instead “when you…. I feel…”; “I’m not sure if that is how you meant it, but that is how I heard it”; “When I said ______, how did you hear it? How did you feel about it?”

- Stepping back and observing, or going out of your way to learn someone’s culture or reasons for acting the way that they do

- Anticipating differences – when there is a gender difference, generational difference, ethnic difference, cultural difference, language difference, take time to lean in their direction beforehand by researching or by asking helpful questions.

- Connecting with someone who just moved from another country? Look up the history and current events, or look up the most common values and cultural distinctives.

- Connecting with someone who is from a different generation? Look up the major events that happened in their lifetime or their generational discintives (more on that in the next post).

Thwarting Crisis Before it Happens:

- Practice Communal Responsibility (see above)

- Use the Power of the BOTH/AND: Often we believe that there must always be a black & white, or an EITHER/OR. Sometimes this is true. But more often than not, when people are involved, there’s a BOTH/AND. Take care not to assume anything and put people in an EITHER/OR box!

- Politics:

- We often assume that you’re either a Republican or a Democrat, but rarely is it this cut-and-dry or black-and-white.

- More often than not it is something like, “I care about stewarding resources well AND I care about women not being abused,” or “I believe abortion is wrong AND I want children of illegal immigrants to be with their families.”

- Relationships:

- “Either you like me or you don’t like me” (again, rarely is it this cut-and-dry).

- More often than not it is something like, “I like spending time with you AND I dislike it when you don’t listen to me or talk over me.”

- Politics:

- Mine for Conflict: Do not wait for others to tell you there is a problem; look out for problems and address them when you see them! To be clear, this is a gift to offer to others – the hope is that they’ll also pay attention to their own problems and tell you when there’s a problem. But again, be an awesome leader and also don’t wait for them!

- Look for the problem, and when you find it (or think you’ve found it), name it in front of your community! See if anyone latches onto this or confirms it.

- Examples:

- “I think we might be having a miscommunication around what we mean when we say ‘social distancing’. How are you defining ‘social distancing’?”

- “We seem really tired and distracted. Do we need to take a break for a few minutes?”

- “When I say I want you to ‘keep me in the loop’, I do not mean ‘send me all of your emails’; I mean ‘give me an update a paragraph long once a week on what has happened’.”

- “When I say ‘tell me what happened’, I always mean ‘to the degree you are comfortable’. I don’t want you to feel obligated to share more than you are ready to share!”

- Warning: You can ‘overfunction’ in this by assuming there is always conflict and by constantly thinking fearfully/anxiously about how to fix the problem, or by trying to invent all the ways in which people might possibly have a problem with you or with the system you are in charge of. Choose to pay attention to the moments when things feel off, and otherwise feel free to still allow others to bring their problems to you when they happen.

- Interrogate the direction to its natural end: Note where you/they are in a situation. Ask yourself (or your community), “what happens if we stay here or keep doing down this path?” Keep asking that question (“then what?”) until you reach the ‘end’. Is that an end you want? There will likely be multiple possible endings, so are they collectively what you want?

- If so, great! Keep it up.

- If not, consider what needs to change, and then make steps together in community towards that change.

What if you’re already in crisis?

- Go back to part 1 of this series. Meet with the person/people. Name the dissonance. Green line. Yes, you can do this as a whole community if it’s a problem that impacts the whole community.

So what do you think? What of this looks easy? What of this looks hard?

If you’d like to practice situations where you could try to create spaces for others to green-line, try these case studies below!

Case Studies:

Feeling anxious as you read these scenarios? Go back and glance over the foundations again!

You are in charge of a team of friends who play volleyball on the weekends. A newer friend has joined the team. This new friend is very sociable and clearly likes the group; the group, generally speaking, enjoys this new friend. However, this new friend is loud. He always speaks confidently and at a volume higher than everyone else in the room. You can tell by your team’s facial expressions when he speaks, and by the surprised look from other teams, that his actions are considered annoying, and at best, tolerable. Additionally, this new friend tends to take over conversations and not pause to hear other people’s input. He has even tried to tell the team how to practice and what they need to work on, despite the fact that you are the leader. No one has said anything to him or to you yet.

What do you do?

- Interrogate the direction to its natural end. If you stay as you are now, what might happen? Is that what you want?

- If you were to change anything, what would you change?

- How would you go about making space to enter into this conversation well?

You are a manager at your job, overseeing trainees and staff. You are seeking to hire a new trainer to help you in supervising the staff. One of your staff has applied but does not meet the requirements because they are not available at all the right times and because they do not yet have any experience training anyone in any way. You cannot give them the position at the moment, but you can offer opportunities for them to practice training new staff in their current role and you can invite them to apply next year if their skills and availability are improved.

How do you approach telling your staff that they did not get the job?

You are a political moderate who believes that the events of January 6th, 2021 at the Capitol were an insurrection, and that President Trump should have been successfully impeached. You have several friends and family who believe differently, who you know well and who you care about, and who are posting on social media about what they believe to be an injustice towards President Trump and to themselves. You have trust built with them, you care about them, and you feel morally obligated to say something, so you have decided that you will respond. How can you enter into the conversation in such a way that you might be able to green-line AND possibly have them green-line through the conversation as well?

- Start with what your goal is: do you want to change their mind? Prove them wrong? Understand? Make sure that you are not complicit by saying your piece?

- How would you frame your response so that you might be able to create space to have the most healthy conversation possible?

- What format would you choose to have this conversation? Why?